This post is part of a series on addressing the problem of human evolution. For a general introduction to the project, click here.

Steelmanning the argument: Why it's important

In this post, the broad question I'll attempt to answer is- why human evolution is a problem for Muslim apologetics. This would essentially consist of discussing all the putative evidence for evolution. I'm sure we've all heard of different lines of evidence for human evolution- the fossil record of hominids, high degree of similarity between humans and other creatures (especially chimps), so-called 'vestigial' organs and genetic elements in our body (like "junk" or non-functional DNA), etc. This post is not going to be a simple enumeration of this evidence. Such treatments are widely available on the internet, and a quick Google search will be more than enough for that purpose. What I do want to attempt here is to frame the evidence in a way that really brings out their evidential strength.

Let me spend a little more time to explain why such an exercise is important.

Popular, unsophisticated presentations of the evidence for human evolution often take the form of "talking points"- 99% DNA similarity between humans and chimps, what's the appendix doing in our body, why do our genomes share errors with other primates, and so on. When presented in this naive fashion, the savvy creationist can usually counter all of these objections point for point, without breaking much of a sweat either. However, I believe these popular presentations fail to communicate the true evidential strength of human evolution. As such, when expected to interact with these claims, the creationist interlocutor often misses the point in his responses. This misunderstanding of the evidence- the thrust- has led to the growth of a cottage industry of bad (or at least, inadequate) responses to evolution.

This is why I believe it's essential to first understand precisely what the evidential strength of human evolution is. Not only is this understanding a prerequisite to developing any good response to the problem (to avoid strawmanning), but also- and more importantly for my purposes- teasing out the thrust of the evidence in this way would clearly delineate what we must do to meet the burden of proof. A satisfactory response to human evolution must be built around the defined contours of its evidential challenge. As such, this post will be important in laying out the theoretical groundwork for the argument I eventually develop.

|

| In much the same way that molds determine the shape of desserts, the evidence determines the shape a good response must take. Really in the mood for bad analogies today |

So to that end, here's my specific game plan. I'll attempt to explain two concepts which I think are misunderstood (or under-emphasized) in discussions of the evidence for human evolution- one, the problem of gratuitous similarity, and two, evolution as an inference to the best explanation. In the course of clarifying each of these concepts, I'll also talk about some common responses to evolution, and show that they fail precisely because they fail to understand these two issues. Finally, I'll discuss the exact shape an adequate response to these problems must take, based on the foregoing discussion.

Two tiny disclaimers before we jump into this:

1. There's a population genetics-based argument against the creation hypothesis, which claims humans couldn't have originated from a single original couple. I'll discuss that argument as a part of this series, but it won't be relevant for our purposes today.

2. In this post, I use "evolution" and "human evolution" interchangeably- but know that I'm talking specifically about human evolution in each case.

The problem of gratuitous similarity

A lot of the evidence for evolution can be simply summarized as follows: humans are very similar to non-humans. The human genome is extremely similar to the chimp genome, certain aspects of the human anatomy is very similar to non-human ones, there are creatures in the fossil record that look very similar to humans, etc.

A lot of the time, popular presentations of the evidence can be reduced down to just that. Posed in that way, this objection isn't all too difficult to answer. Most cars have four wheels, so they are clearly similar in at least two ways: they have wheels, and they have four of them. This doesn't mean they evolved one from another- just that wheels are essential for them to function as cars, and four is a very pragmatic number of wheels for a car-like structure to have. So the similarity here can easily be explained on the hypothesis of shared functional constraints. Common design, one wants to say.

However, the similarity argument goes deeper than this. This is because the similarity between humans and non-humans has a peculiar feature: it is gratuitous.

Gratuitous means meaningless. Going back to the car example again- the four-wheel similarity between two cars is meaningful- they are similar because the shared features serve an essential purpose. They had to have been that way. What, then, does meaningless similarity look like?

Let me explain the concept with the aid of an analogy. I readily admit that the analogy is quite forced, but it's what I could come up with. I'll replace it as soon as I think of something better, I promise.

Take a look at the two cars below.

|

| I stole the image off of Google and put the blue marks with MS Paint |

The cars clearly seem to have a lot in common- wheels, mirrors, lights, seats, etc. However, there's a type of similarity between these two cars that are not like the others. There's a light blue mark- think of it as a strip of raised metal- at the back of both cars.

This similarity clearly doesn't serve a purpose. The blue strip isn't performing any function. In fact, this looks like a factory error- the metal being raised in that sort of unaesthetic, uneven fashion clearly gives off that impression. This type of similarity really is meaningless. Gratuitous.

A lot of the similar features between humans and non-humans can be characterized in just this way. We could've appealed to common design to explain shared features if they were required to perform the same function (there's a caveat though, read below). But we have a lot of features, especially in our DNA, that look like mistakes, errors, quirks, or kinks. Both human and chimp genomes are replete with corpses of viruses that once infected us, or shared mutations in otherwise functional genes, or bits of DNA that can move about willy-nilly but are otherwise non-functional. They are akin to that bit of off-color raised metal against an otherwise smooth surface. The fact that we share these features with other creatures in such a gratuitous way means it cannot be explained by citing shared functionality- common design- alone.

The creationist has a response to this, however. What if, he points out, these shared genetic elements aren't non-functional at all? What if they do have a function that we're either ignoring, or would be discovered in the future? Doesn't that solve the problem?

To illustrate the problem with this counter-response, let me modify the analogy a bit further- which will render it even more grotesque.

Let's say after close inspection of the car, we observe the following:

|

| The weird blue rectangles are meant to represent drawers. Please just play along |

Voilà. The blue raised bits of metal in the two cars that we thought were non-functional, actually seems to have a purpose- if you yank it hard enough, it opens up into a drawer at the back of the car where you can store stuff. So it does have a function- it's a drawer latch. Does this mean this similarity is no longer gratuitous?

No, of course not. Even if these two bits of metal function as drawer latches, this still doesn't answer everything about why they're similar. For starters, why are they both that particular shade of blue? Clearly, that bit of similarity- both of them being blue- doesn't have any functional significance. The drawer latches did not need to be such a specific color in order to function the way they do. So just because the shared feature itself has some function, as long as it has some properties that doesn't contribute to that function- they would still constitute an example of gratuitous similarity.

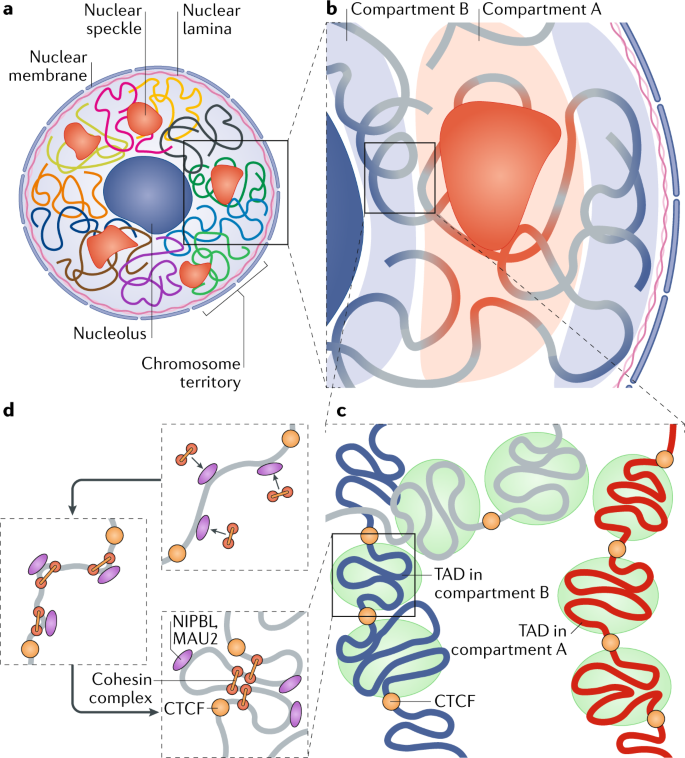

Let's export this example in the case of genetics and human evolution. The human genome has a high degree of similarity with the chimp genome, and large swathes of it aren't coding for proteins. However, it's plausible that all that extra genome is being used for something. For example, researchers (1, 2) have pointed out that the "bulk" of the genome is used to control the size of the nucleus. So while the sequence of the genome may not be very important, we still need the genome to be of a certain size in order to give the nucleus its appropriate size. This, in turn, is important for the cell. There's also some evidence that the genome needs to be "packed" in a certain way in the nucleus in order to have the specific functional roles that it does, and that packing requires the genome to be of a certain length. Meaning, all of that extra non-coding sequence in the genome is probably functional, only not in a sequence-specific way.

|

| The genome is folded and arranged in particular compartments in the nucleus, and this arrangement has functional consequences. DNA here is working not as a code, but as structure. Picture taken from this paper |

However, even if these shared parts of the genome are functional, that still doesn't explain why they have the specific sequence that they have. If their functionality is not sequence-dependent, then why do they have the same sequence? Compare with: if the functionality of the car drawer latch is not dependent on its color, why are they of that same peculiar color?

Todd Wood is a geneticist and a young-earth creationist who is generally very critical of bad creationist arguments. He responded to this "appeal to functionality" argument in a similar way on his blog:

A more subtle mistake is the insistence that vestigial organs have no function, that they are true evolutionary leftovers that are just waiting to be eliminated from our bodies. This leads to the equally fallacious response that by demonstrating a function - any function - the vestigial argument is nullified. In response to this reasoning, Steve Matheson made a great analogy to the function of a 1989 Yugo: Just because you can turn a Yugo into something useful, like a mailbox or port-a-potty, doesn't make it any less a vestigial car. In fact, it makes its car-ness all the stranger, since its automotive attributes have nothing to do with its function as a mailbox or whatnot. See my point? Having any function does not mean something can't be a vestige. I personally prefer to use the old term rudimentary structures for what we now call vestigial organs.

This underscores the problem of gratuitous similarity: It's not just that humans are very similar to chimps, it's that this similarity has no functional explanation- it could very well not have been.

And yet, here they are. And that's the problem.

In fact, this point can be strengthened even further. Even if one can show that a shared feature is functional in every way- that the drawer latch needs to be blue for some reason (let's say it's light activated, and only responds to a certain wavelength- look, I warned you this analogy would be weird)- this still doesn't solve the gratuitousness problem. This is because these ends could have been achieved in many other ways. If the function of the blue strip was to function as a drawer latch, couldn't the car have had a drawer or a storage unit in so many other ways? Why this way in specific in both cases?

This argument applies all the more to human design. There are so many different ways in which biological purposes can be achieved. The fact that the exact same features are being used in humans and non-humans to achieve the same ends- when that end could've been achieved differently (perhaps more efficiently)- still indicates gratuitous similarity. The biological anthropologist Jonathan Marks, in his book What it Means to be 98% Chimpanzee, sums up this point succinctly:

The 98% genetic correspondence of humans and chimpanzees does have a consequence with which hard-core creationists must wrestle— namely, that either humans and chimps do share a recent common ancestry, or else they have been independently zapped into existence by Someone lacking a great deal of imagination.

Basically, there are so many ways in which we could've been functional. The fact that we're functional in exactly the same way as chimps, is gratuitous.

This is what I call the problem of gratuitous similarity. The true evidential strength of this observation will become more apparent when considered together with the material below. However, the foregoing discussion has made the following point clear: a naive appeal to common design, even when joined with a claim of pervasive functionality of all of our features, cannot account for this problem. One would need additional argumentation to address this- a more nuanced creation hypothesis, perhaps.

This insight will be useful down the line when we develop our argument against human evolution.

Inference to the best explanation

We humans show significant similarity to a lot of different species- living ones, like chimpanzees and other primates, as well as extinct ones, like australopithecines and early members of Homo genus.

In addition to the aforementioned gratuitousness, there's another curious feature of these similarities relevant to this discussion. These similarities always form a pattern. And that pattern is best explained by evolution.

Consider the fossils. Australopithecines (left below) are anatomically less similar to humans than other hominids, and they show up first in the fossil record. Members of early homo (right below- Homo habilis) are somewhat more similar to us, and they show up next. Then comes the somewhat more "advanced" Homo ergaster, followed by Homo heidelbergensis or archaic Homo sapiens, followed finally by anatomically modern humans. The pattern that emerges from this is, creatures that are more similar to us show up later in history, while those more distant ones show up earlier. There's no real exception to this.

The point of this observation is: this pattern of similarity between humans and non-humans is very conducive to an evolutionary inference- simpler early, more advanced later. On evolution, this is exactly how we would expect the evidence to look.

Other observations about the fossil record only makes this conclusion stronger: for example, the most "primitive" technology is the earliest to appear in history, followed by a degree of advancement, followed by another degree still, and so on. So it's not like anatomical sophistication alone shows this pattern- technological advancement also broadly aligns with it. All of this, again, is exactly what you would expect on evolution.

Let me now substantiate the same point with the genome. Earlier I alluded to "virus corpses" shared between human and chimp genomes. This class of genetic elements- the endogenous retroviruses- are widely considered to be some of the strongest evidence for common descent. These elements enter the genome when viruses infect the cells and integrate their genomes into that of the host. As such, these are parasitic elements that usually confer no functional advantage. The fact that these elements are found to be inserted in both human and non-human genomes at the same locations is an example of gratuitous similarity par excellence. See this article for a brief description on this topic.

However, this similarity is not only gratuitous, but has a specific pattern. Look at this image that I took from an old paper (I first got wind of it from talkorigins):

|

| This paper came out in 2000, but serves our purpose well |

This is a family tree of humans and the great apes. Each arrow signifies the existence of a specific type of endogenous retrovirus (ERV). These elements can be clearly seen to follow a specific pattern of distribution: the same elements are always shared between closely related species, and they never skip close family members for distant ones. You never see an element that's, for example, shared between humans and gorillas but not with chimps, who are closer to us. Never between chimps and orangutans, but not gorillas. So the pattern of distribution of these elements, themselves examples of gratuitous similarity, is very strongly indicative of evolution. Humans share a lot of ERVs with gorillas, but even more so with chimpanzees- because humans and chimps had a common ancestor and are part of the same family tree.

Todd Wood, whom I referenced above, makes the point forcefully in the context of the genome similarity between humans and chimps (reference):

[T]he mere fact of similarity is only a small part of the evolutionary argument. Far more important than the mere occurrence of similarity is the kind of similarity observed. Similarity is not random. Rather, it forms a detectable pattern with some groups of species more similar than others. As an example consider a 200,000 nucleotide region from human chromosome 1. When compared to the chimpanzee, the two species differ by as little as 1- 2%, but when compared to the mouse, the differences are much greater. Comparison to chicken reveals even greater differences. This is exactly the expected pattern of similarity that would result if humans and chimpanzees shared a recent common ancestor and mice and chickens were more distantly related. The question is not how similarity arose but why this particular pattern of similarity arose.

The upshot of this is the following. Humans share gratuitous similarity with other creatures in a pattern that's explained very naturally and comfortably on an evolutionary hypothesis. If evolution were true, these are exactly the patterns we would expect. In other words, these features are best explained on human evolution.

This distinction is important to understand. Many people, due mostly because of popular presentations of the evidence, think human evolution is a sort of deductive argument- the conclusion follows logically from the evidence. However, this is an unreasonable burden of proof for any hypothesis to bear. No theory needs to be preclude the logical possibility of an alternative explanation in order to be successful. Rather, human evolution is considered an inference to the best explanation- in terms of explanatory power and scope, simplicity, elegance and predictive capability- it's the best game there is.

Put differently, these lines of evidence don't logically preclude a creationist hypothesis from being true. God could've created humans separately, and yet for some reason, kept these markers of evolution in place. That hypothesis, together with the evidence, can both be maintained without logical contradiction. There are, however, two interrelated problems with this. First, these lines of evidence don't really "fit" naturally in a straightforward creationist hypothesis. After all, a creationist has no explanation for why these gratuitous similarities exist in the pattern that they do. Second, there's another hypothesis that explains the data much better. In scientific (and everyday) reasoning, an uncomfortable fit with the data, and the presence of a more compelling hypothesis, are two really strong indicators that the theory is probably false. Alternatively, evolution is true because it's the best explanation.

This is a basic point in epistemology that I expect my audience to be familiar with, so I won't belabor this point further. Let me round off this section with a quote from the University of Washington computational biologist Joshua Swamidass that I think really captures the intuitive punch of this problem (reference):

Let us imagine that God creates a fully grown tree today, and places it in a forest. A week later, a scientist and a theologian encounter this tree. The theologian believes that God is trustworthy and has clearly communicated to him that this tree was created just a week ago. The scientist bores a hole in the tree, and counts its rings. There are 100 rings, so he concludes that the tree is 100 years old. Who is right? In some senses, both the scientist and the theologian are right. God created a one week old tree (the true age) that looks 100 years old (the scientific age). Moreover, it would be absurd for the theologian to deny the 100 rings that the scientist uncovered, or to dispute the scientific age of the tree. Likewise, the scientist cannot really presume to disprove God.

Instead, the theologian should wonder why God would not leave clear, indisputable evidence that the tree is just a week old. My question to the theologians: Why might God choose not to leave evidence that this 100-year old tree is on week old? Alternatively, why might God choose to leave evidence that the week-old tree is 100 years old? [Emphasis in original]

Burden of proof

Putting everything together, the problem of human evolution is as follows.

1. There are numerous examples of gratuitous similarity between humans and other creatures. These examples are mined from different fields of scientific research, particularly comparative genomics and paleoanthropology.2. These similarities cannot be explained on a creation hypothesis, except in an ad hoc way that adds unwarranted assumptions to the core hypothesis.3. These similarities can be easily and naturally explained on human evolution.4. (From 1, 2 and 3) These similarities are best explained on the human evolution.5. Human evolution is probably true.

As mentioned at the beginning of this post- teasing out the main evidential thrust of the argument aids in conceptualizing possible solutions.

Things to come

If one takes the scientific evidence at face value- as I'll be doing, as mentioned in the last post- the only recourse for us is to attack (2). The burden of proof, then, is to provide a creation hypothesis that can explain this evolution-esque pattern of gratuitous similarity in a non-ad hoc way. Put differently, if one can produce a creation hypothesis that can easily and naturally explain this evidence, to the extent they follow from the standard predictions of the hypothesis- we can then say that evolution is not necessarily the best explanation of the facts, and, at least, there's a plausible contending hypothesis that can also be accepted without falling into irrationality. This is the minimal burden of proof that needs to be met in a good response to human evolution.

In this series, therefore, I'll be attempting to construct just such a hypothesis. To this end, I'll drawing on evidence from Islamic scripture and employ plausible theological reasoning. My main goal would be to show that this hypothesis is not ad hoc, and follows naturally from what we know about Allah and His actions (based, again, on scripture and theology). I'll then examine the specific lines of evidence for evolution once again (from paleoanthropology and comparative genomics), and account for them in light of this hypothesis.

While I believe this alone would achieve the minimal goal of providing a response to human evolution, I plan to do an additional, important thing as a part of this series. I will produce evidence that there are certain lines of evidence, just as significant (if not more) as the sort we've been discussing in this post, which cannot be explained on the human evolution hypothesis, but follow naturally from the creation hypothesis. If successful, this will leave us with the following two facts:

1. The "garden variety" evidence for evolution is explained just as well on the creation hypothesis (that I'll be defending),

2. Certain additional evidence can be explained easily and naturally on the creation hypothesis, but not on evolution.

The upshot of these two facts put together is, the creation hypothesis, and not the evolution one, is in fact the inference to the best explanation, just in terms of its explanatory scope.

All in all, my series would constitute a positive case of the creation hypothesis, and not just a defense, inshaAllah. In the next several posts, however, we will engage in a "fun and games" segment- where I critically analyze some extant unsuccessful attempts to address human evolution.